Birmingham / NUX

After he left the army, Charles returned to civilian life and his job as a clerk with Birmingham Corporation. He joined the Labour Party on his first day of demobilisation and soon became involved with several socialist organisations.

"I remember standing in front of a coalcart in Birmingham Bull Ring one Sunday night in February 1919. It was the day after I left the army. One of my worlds - the world of the war - had just ended. Another was just beginning. I was a little nervous of this new world. It all seemed so strange. There were no signposts to show which way to go. I listened to the man on the coalcart who was speaking. He was thinking of this new world too. He was saying how it could be a better world, a happier world, a healthier world. I joined the Labour Party before the meeting ended. I had been a good solider. I wanted to become a good citizen. I felt that in joining the Labour Party I had become one."

(Charles Leatherland, Daily Herald, 1949)

NATIONAL UNION OF EX-SERVICEMEN

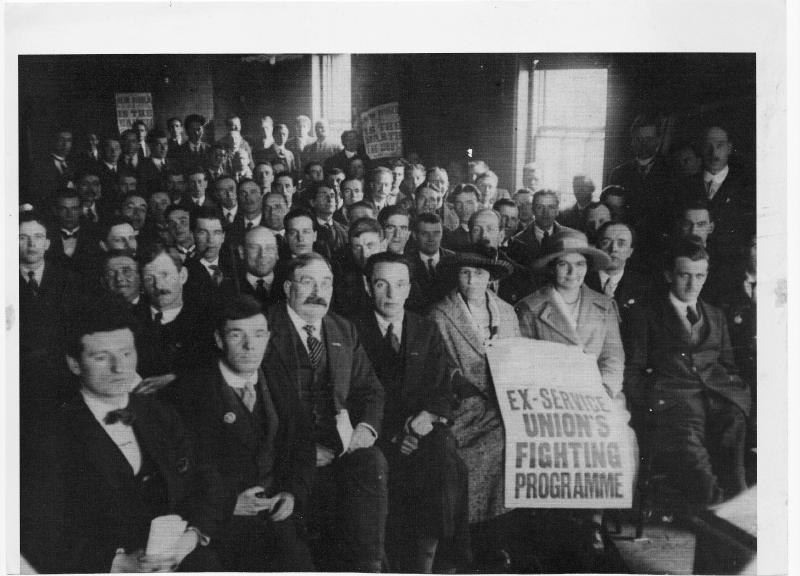

Leatherland - bottom left in bow tie - at a meeting of the National Union of Ex-Servicemen in 1919

Leatherland began campaigning for better treatment for soldiers who had returned from the war. Many ex-soldiers felt betrayed by the way they were treated by the Government. He became one of the founder members of the National Union of Ex-Servicemen and stood for the Presidency of the Union.

He wrote a weekly column in the Birmingham Town Crier newspaper on ex-servicemen's issues, and often spoke at political meetings and rallies in the Birmingham and Wolverhampton area. For example on 22 April 1920 he spoke at a meeting of the Birmingham City Independent Labour Party on "Armed Force and the Coming of Socialism".

The National Union of Ex-Servicemen (NUX) was formed in early 1919 as a socialist association for former soldiers. Within six months it had over 100 branches and claimed to have nearly 100,000 members. But by the end of 1920 it was almost defunct. In the words of its only historian, the late Dr David Englander of the Open University, "its records were lost, its achievements forgotten, its objects misunderstood".

Dr Englander points out that the socialist left in Britain regarded the army "with a mixture of fear and contempt". Armies had no trades unions and no tradition of working class culture even though most soldiers who fought in WW1 were from the working classes. The labour movement in England found it very hard to portray itself as the 'soldier's friend' during the First World War and after.

Militant ex-servicemen's organisations such as the National Federation of Discharged Soldiers and Sailors (1916) were formed . Another organisation, Comrades of the Great War, was formed in 1917. Soldiers returning from the war, many wounded in action, many shell-shocked, many unable to find work were often regarded as a threat to society. Many ex-servicemen felt angry and betrayed. Army pensions were inadequate, compensation for soldiers disabled during the war was poor. The atmosphere of fear which many people felt was sharpened by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917. Could Britain be next ?

The National Union of Ex-Servicemen (NUX) had several leading figures who later became famous in other ways :

John Beckett who later became a Labour MP and a member of the British Union of Fascists

Ernest Mander who became a writer and academic in New Zealand.

John Beckett was a former army corporal who was invalided out of the army in 1916. In the 1920s he shared a house with future Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee. He achieved notoriety in 1930 when he seized the mace during an angry debate in the House of Commons.

The NUX was a campaiging organisation. NUX branches tried to get justice for disabled soliders and their dependants. The Birmingham NUX took up the grievances of street traders - many of whom were ex-servicemen trying to make a living. According to Dr David Englander

"In the eighteen months after its formation, the NUX had conducted a vigorous propaganda campaign across the length and breadth of the land : an estimated 47,000 meetings had been held and a vast quantity of literature distributed".

Leatherland was not a militant agitator and there is no evidence that he ever flirted with Communism. But I did find him quoted in a secret Home Office Directorate of Intelligence Report to the Cabinet on Revolutionary Organisations in January 1920 (released by The National Archives). The report examined amongst other things the extent of revolutionary feelings among ex-service men. The writer of the report said that :

" Ex-Colour Sergeant Major C. E. Leatherland, Chairman of the Central Branch, who has been nominated for the office of General President of the Union, told my correspondent recently that the Union was determined to obtain its demands by fair means or foul, and added "We are going to the Government with a whip in our hands ".

Despite this apparently dramatic statement, the report concluded that there was little revolutionary sentiment in the country, and there is no evidence that Leatherland was involved in provoking revolutionary ideals, although clearly the security services were keeping tabs on the National Union of Ex-Servicemen. However, many members of the NUX did end up joining the Communist Party.

National Union of Ex-Servicemen Badge

At the NUX Easter Conference in 1920 Leatherland, who was by then the Midlands Organiser, stood for General Secretary of the NUX, although John Beckett was elected.

By 1921 the National Union of Ex-Servicemen had fizzled out, although at its peak it claimed a membership of over 100,000 former soldiers. The British Legion later took over as the leading ex-servicemen's organisation.

Leatherland's experiences in the National Union of Ex-Servicemen gave him an apprenticeship in journalism, together with experience in public speaking and contacts in the Labour movement, all of which were to prove useful in his future career in national journalism, local government and politics.